My memories of the 1950s

BORN in 1953, I consider myself fortunate to have access to images and publications from the 1950s that help me recall my early years. I owe this to my parents, who not only took photographs but also collected books and other printed materials, carefully storing them for the future.

These artefacts serve as powerful memory triggers. Neuroscience suggests that when we view an image, the brain rapidly links it to stored sensory experiences, emotions, and contextual cues—a process involving the hippocampus and amygdala, two regions central to memory and emotional processing.

This instinct to record and preserve memories also runs in my family. Apart from my parents who were avid chroniclers of their work and hobbies, my grandfather compiled a three-volume Attempt at Autobiography; and my uncle was a pioneer poet and novelist in Singapore. Their habits of documenting, whether through photos, writing, or literature, shaped the way I now think about memory, legacy, and storytelling.

The twelve images in this exhibit were chosen for their ability to evoke vivid personal memories. Many of these memories are shared with my family. My late parents and grandparents would have remembered even more, with many layers of memory tied to these images and the places they show.

I never felt totally at ease in the comfort and luxury of the wealthy. I often felt guilty when I saw how many others struggled, and there were many rules and expectations to follow. Over time, I began to discover my own path, which led me to study sociology and ultimately choose journalism and publishing as my career.

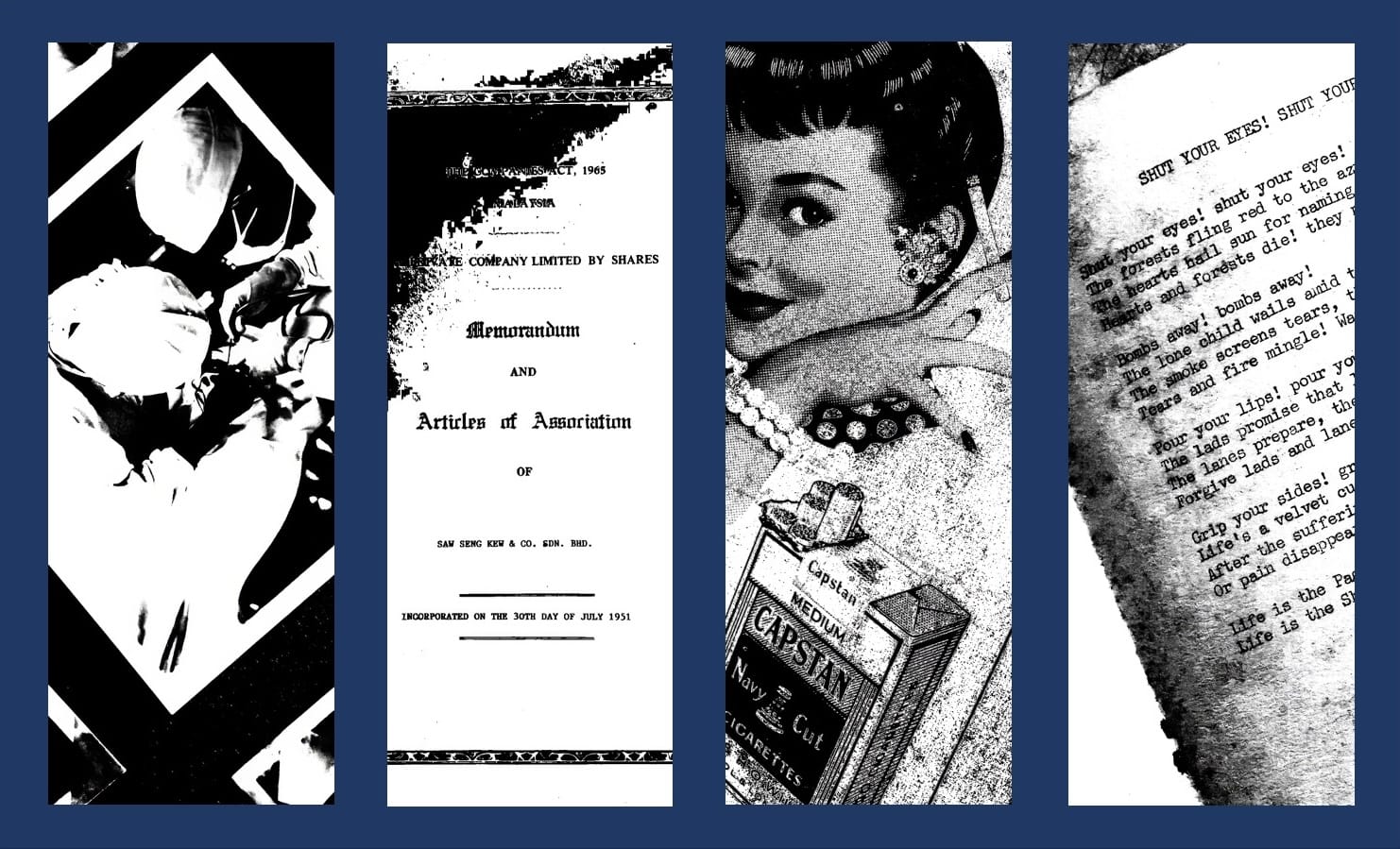

Alveolectomy: My dad, Dr Lim Teik Ee, who trained as a doctor but settled for dentistry due to financial reasons, told me he used to operate on cadavers. We didn't have photos of that, so I thought a shot of him performing an “alveolectomy” would serve as a substitute. It was taken in 1950 when he was a student at the University of Malaya in Singapore. The “minor oral surgical procedure involves removing or reshaping the alveolar bone, the ridge of bone in the jaw where teeth are rooted”.

M&A SSK & Co: During the 1990s, I witnessed my mother and aunt struggle to keep their father’s dormant company alive due to its heritage value and as a family legacy. Incorporated in 1951, Saw Seng Kew & Co Ltd was a huge company in its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s. I decided to take it over and have kept it going, albeit dormant, for the last 20-plus years. Last year, I reactivated it as a fledgling research and publishing company.

Capstan: In the 1950s, cigarettes were often unfiltered, and many brands came in tins. Capstan was one; another was Player’s. Both were Navy cuts, a way of making cigarettes where the tobacco was pressed tighter than usual, producing a richer, slower-burning smoke. Both my grandfathers smoked them.

Shut your eyes: My uncle, Lim Thean Soo, was a poet and novelist who, nevertheless, spent much of his life as a civil servant in Singapore, rising to the level of Director-General of Customs before his retirement. Much of his writing was done after his retirement; however, I managed to find a copy of his self-published Poems (1951-1953). The book was a gift to my dad. The poem, “Shut your eyes! Shut your eyes!”, was about World War II, specifically the Japanese invasion. It concluded rather grimly: “Life is the Pageant: Death the Finale. Life is the Shadow: Death the Reality”. Read more about him here.

Kam Yong was my amah, “nanny” from post-confinement. Extremely loyal and loving, she stayed with us for a few decades, caring for my three other brothers as well. For most of our pre-teen years, she slept in the same room as me and my brothers, making sure we were healthy, spick and span. Once a week, we would force ourselves to take one large bowl each of her double-boiled soup of liver or chicken. She retired to her kongsi in the late 1970s, visiting us occasionally. I have a photo of her carrying our daughter when she was one year old in 1981.

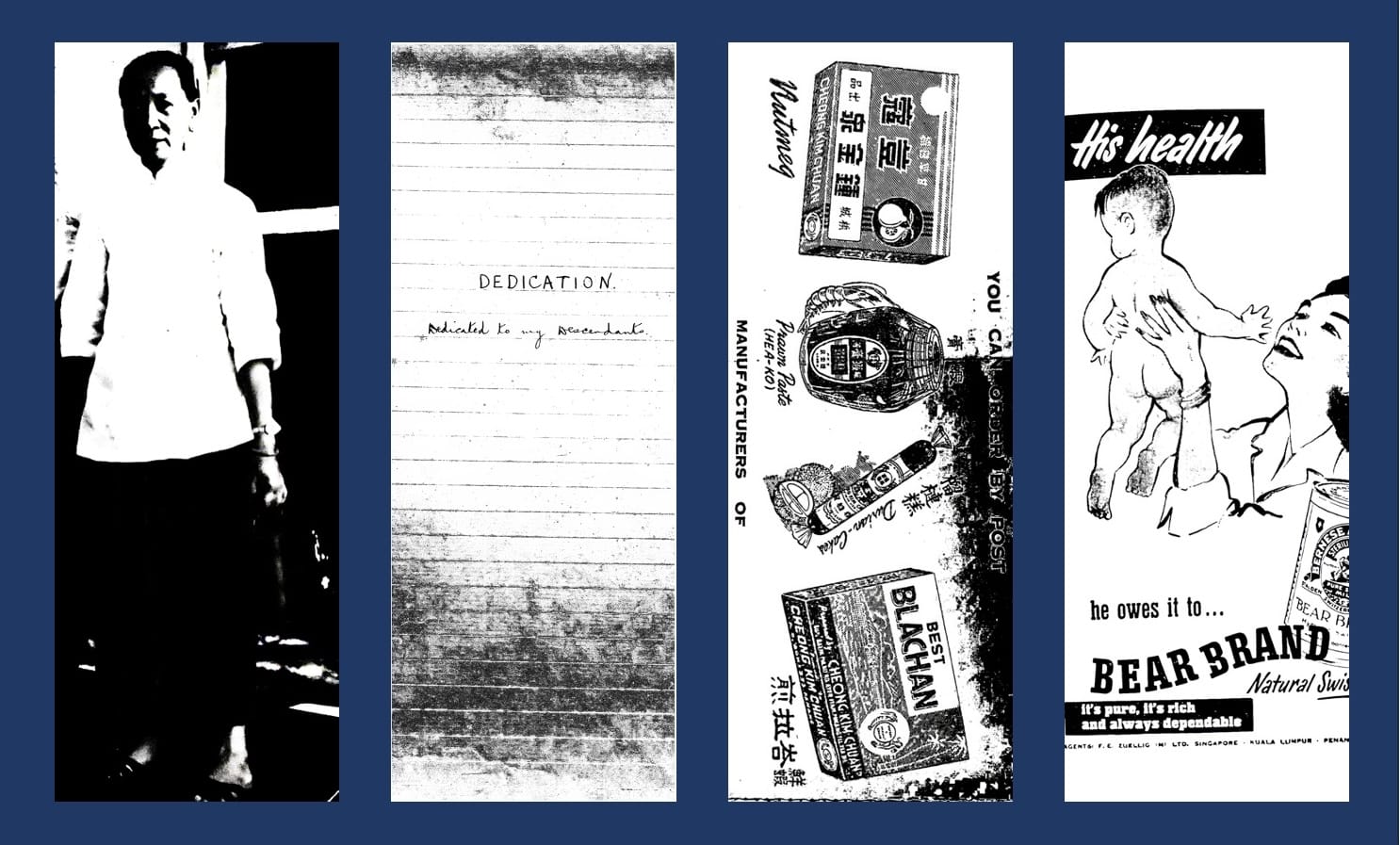

Dedication: My paternal grandfather, Lim Ewe Lee, wrote the following in his memoirs: “The autobiography of a very ordinary clerk who is almost a nonentity will certainly not make interesting reading, and as such, will not be inflicted upon the public by being added to the millions of existing volumes already printed. It will, therefore, not see the light of day in a publisher’s house. The idea is undertaken solely for the purpose of recording truthfully the private life of the writer, for home consumption only, and, in time to come, if reference is made to this record by his family, it will not have been written in vain.” This was very touching, but it came across as too self-effacing. He was Chief Clerk of the Chinese Protectorate, the highest civil service position for “Asiatics” in Penang, and was awarded an MBE by the British Government in 1949. It took me over six years to have the handwritten books input, copyedited, and put on a family-only website.

Cheong Kim Chuan: This brand always brings back memories of our family trips to Kek Lok Si temple to feed the tortoises. CKC, which is still known for its nutmeg products, belacan, and rojak sauce, used to be along the winding steps to the temple. It closed after Covid and changes to the walkway. Back then, the path was lined with beggars, and we would bring small wallets filled with one-cent coins to give out. You could buy a simple meal for just 10 cents. At the tortoise pond, we purchased potato leaves and kangkong for the tortoises, as well as biscuits for the fish nearby. Even years later, in 2007 and 2008, when I organised the Rasa Rasa Penang food hunts, CKC was always a must-visit, especially the shop near Kek Lok Si, not the one in Air Itam.

Bear brand: Before reconstituted milk from brands like Dutch Lady and Nestle, there was Bear Brand. It was the milk of choice wherever “fresh milk” was required in recipes, many emanating from the West. The sterilised milk came in tins and originated from Switzerland.

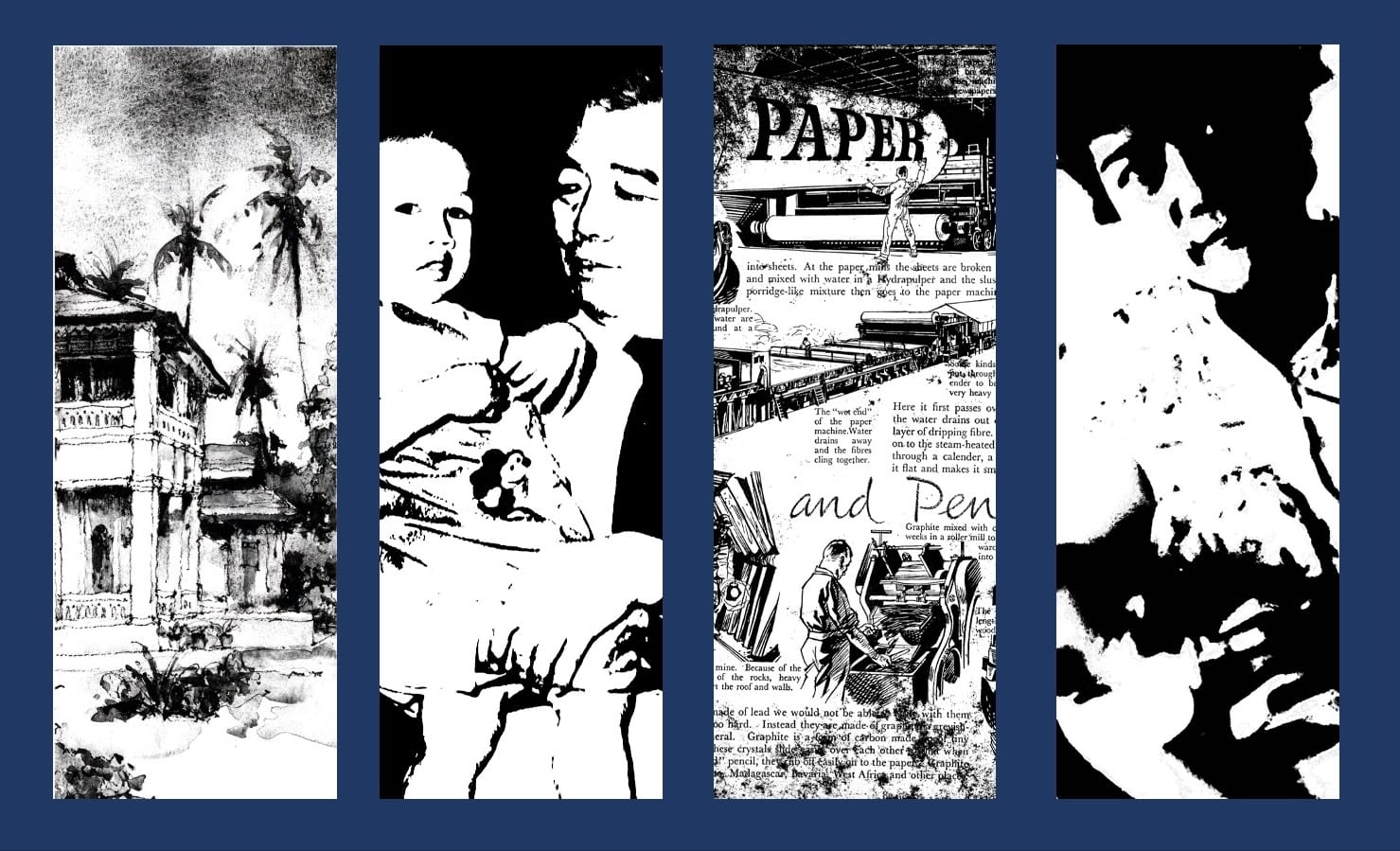

Peak View: I grew up in this house along Gurney Drive. It was a boy’s dream. A huge garden with fruit and ornamental plants, where one could learn the intricacies of horticulture from a father fascinated with plants, especially orchids. Later, from the mid-1960s, a large group of friends, neighbours, and children of the drivers and gardeners took us through all the street games and cycles (marbles, top, cards, etc.) and field sports.

Granddad: As the first grandchild, Granddad Seng Kew gave me a lot of attention. He took me to his club where he played cards with friends, and I often spent time in his office on Beach Street. One day, I told my grandma that he didn't really work at his office, since he spent most of his time talking on the phone. At that time, he was a rubber broker.

Paper and pen: My father ensured we were surrounded by books when we were kids, but I didn’t enjoy reading then. Picture encyclopaedias were an important source of general information; this is a page from one of them. Additionally, a grand uncle of mine owned and operated a printing company called Premier Press. He would send us the offcuts from time to time. Therefore, there was never a shortage of paper in our house for me to indulge in drawing. It’s a pity none of my sketches is still around.

Mother and son: My brother Siang Ghee was born in April 1957, a few months before Merdeka. This is a picture of him and my mother just after his full moon. He was too young to play with me in the 1950s; however, we got on superbly later, indulging in all sorts of activities the home could offer, including carpentry, gardening, outdoor games, raising dogs and fish, and fishing.

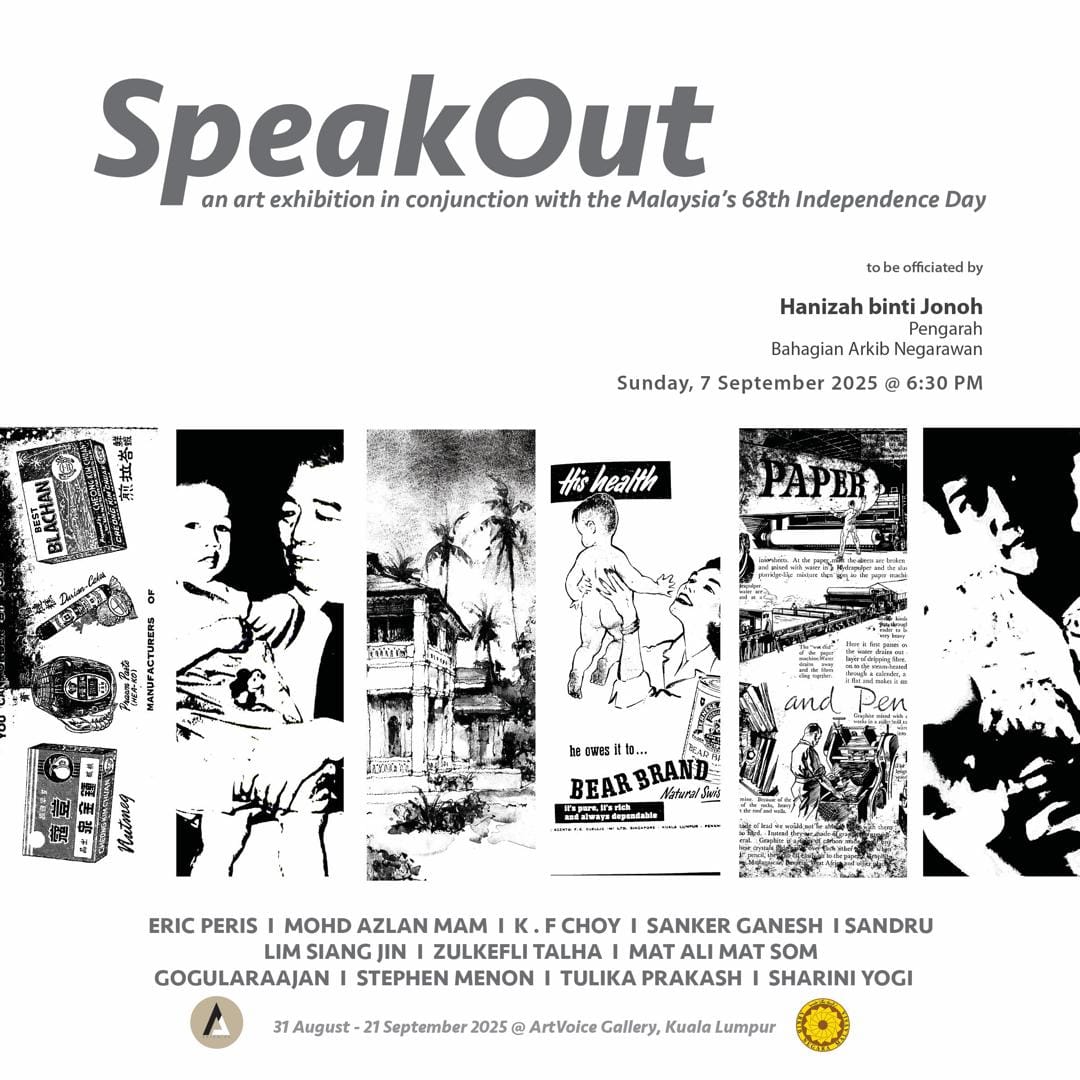

The following are the other exhibits of SpeakOut. They are not run-of-the-mill stuff for Merdeka shows. Each tells a story of the experiences related to the nation's independence.